From Courtesans to OnlyFans

On Nineteenth Century Courtesans, Financial Speculation, and Sexual Capital in the Twenty-First Century

The dawn of the OnlyFans era coincided with the Covid lockdowns. In 2020, the human body could be seen as both a laboratory of infection and a factory for producing sexual “content”. In a strange way, our bodies became both more physical—the terror of the cough on the subway, the internal interrogation of every ache and pain—and more disembodied. The body as an image on a screen was “safe.” Safety First.

Have women, especially young women, been materially changed by the OnlyFans era? The excesses are disturbing—OnlyFans stars Bonnie Blue and Lily Phillips have recently generated virality with extreme stunts and large numbers of partners (Of course, we are only speaking of virality in the disembodied sense here).

Thomas Picketty, in Capital in the Twenty-First Century, popularized the thesis that we had returned to an era like the one in which Marx formulated his ideas, the mid nineteenth century. It is nearly impossible to get ahead financially by waged labor, as it may briefly have been in the twentieth century. The only means of safety is in owning capital.

A body can be capital, but it is surely the most quickly depreciating kind. A beautiful woman who aims to get by on her looks is aware that each passing day entails a markdown in the value of her assets. The frank conversion of face and body to money in the digital era, either through OnlyFans, escorting, influencing, or some combination of the above is neither new nor unique, although, like everything online, it is more extreme.

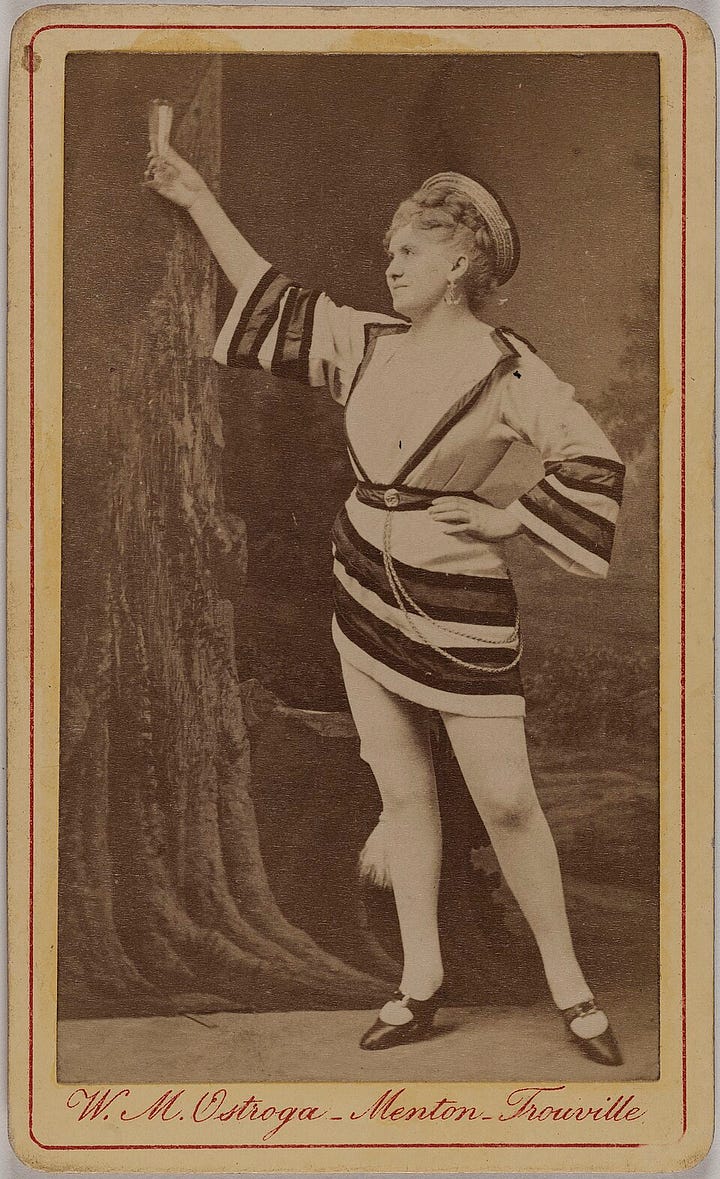

In fact, the last time women selling sex attained such a central place in society and the cultural conversation was the same era that Thomas Picketty writes about. In the middle of the nineteenth century, in wealthy countries, high-class prostitutes became more financially successful than ever, more famous than ever, and thus more openly discussed. They were known by various names, most often courtesans—a rank higher than common street prostitutes, but very clearly not ladies. Were they ruining society? Were they merely a symptom of society’s degeneration at the hands of greedy capitalists? They used the new technologies of the time, including photography, to self-promote. Like today’s OnlyFans models, they existed in a zone of plausible deniability. They were dancers, singers, actresses, milliners—but their actual trade was in their own sexuality. Also like today’s OnlyFans models, they had a similar “look"—instead of today’s duck-lips, fillers, and toned bodies, they were voluptuous, with strong, sometimes almost masculine facial features. They also gave themselves new names—today, it’s Bonnie, Lily, Sofia. Then, it was Olympia, Marguerite, Valtesse.

Their rise was very much linked to the rise of banking and financial speculation replacing land and estates as the major currency of the Western elite. Prior to the nineteenth century, even the wealthiest men had much of their wealth tied up in inherited land and houses which legally could not be sold. Thus, they could only spend so much on women. With the rise of financial speculation, often tied to building projects like canals and railroads, men of all ages and backgrounds were able to amass vast fortunes in cash quickly. Easy come, easy go—money won in a morning by investing in a new South American rail line might be spent in the evening in the company of a fashionable courtesan.

In the same way, the rise of Bitcoin and other crypto assets empowered a generation of young men to speculate financially and blow their quickly acquired assets on, among other things, women. NFTs and OnlyFans rose at the same time, just like impressionism and courtesans.

In the nineteenth century, young women flocked to the capitals, in particular Paris, to engage in their own speculation, with their bodies, not their pocketbooks, as capital. In Grandes Horizontales, Virginia Rounding tells the story of this era through the lives of four women who struck it rich as Paris courtesans. Marie Duplessis, the earliest and in many ways tamest of the women, was dead of tuberculosis before her twenty-fourth birthday in 1847. She emerged from the French countryside into Paris at the age of fifteen, after already enduring a history of childhood sexual abuse. She quickly rose to become the most famous courtesan in Paris, well-known for her demure, elegant apparel and demeanor. Born to a traveling peddler, she died a comtesse. Alexandre Dumas fils, a lover, immortalized her as La Dame aux camélias in a classic novel mirroring her life and death which was itself turned into the opera La Traviata.

As the nineteenth century progressed, courtesans became richer and more brazen. Rounding also recounts the tale of Blanche de Païva, who was born Esther Lachmann to Russian Jewish parents in 1819. By the time she was twenty-two, she had changed her name several times and was already a well-known courtesan. She famously tried to attend an audience with the King and Queen of France at the Tuileries with her common-law-husband, but was rebuffed at the door by a lackey—at which point she broke her fan and threw it in her “husband’s” face in a rage. Many lovers and several husbands later, she died as the owner of one of the finest homes in Paris, Hôtel de la Païva, which stills stands today, and as the chatelaine of a castle in Upper Silesia, Schloss Neudeck.

Newspapers, novelists, and playwrights decried and debated this new class of ultra-rich prostitutes, associating them with societal decay. Frequently, there was anti-semitism mixed into the critiques as it was assumed that Jewish bankers were behind both the rise in speculation and prostitution.

One of the masterpieces of this period is Nana by Émile Zola. I first read it when I was a twenty-year-old in dizzying post-financial collapse New York, and I was entirely shocked at how Zola had managed to inhabit the mind of a young woman. Nana uses her sexuality to destroy the most powerful men in Paris. Rather than show her as a cackling, champagne-swilling villain who enjoys her power, he paints a picture of a woman who is living in a constant state of anxiety, afraid about the next bill coming due, panicked about how to keep her many admirers apart so that she can avoid conflicts and earn enough money to keep herself, nervous about her young child in the countryside, depressed at the prospect of having to sleep with a distasteful man for cash. She is, however, not an idealized, flawless victim of the kind Dickens or Hugo might create. She is petty, small-minded, greedy, and at times brutally sadistic—characteristics that Zola observes come from her wretched childhood in the slums of Paris and early sexual exploitation, which has inculcated in her a desire for revenge on the wealthy men of Paris. He creates a fully rounded female character that is entirely believable—entirely the sort of character that might be created and thrive in such an environ—neither demon or saint.

When will we get the great OnlyFans novel, and who will write it? I hope that it is in progress already.

Sources

Carbonel, M.-H., & Figuero, J. (2003). La véritable biographie de la Belle Otero et de la Belle Époque : ruine‑moi, mais ne me quitte pas. Fayard.

Kavanagh, J. (2014). The girl who loved camellias : The life and legend of Marie Duplessis. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Harvard University Press.

Rounding, V. (2003). Les Grandes Horizontales: The lives and legends of four nineteenth‑century courtesans. Bloomsbury.

Zola, É. (2017). Nana (Tite Fée, Éd.). Createspace Independent Publishing Platform. (Original work published 1880)

Interesting, insightful, and beautifully written!

Brilliant piece. I'm so glad to have stumbled upon it. Great OnlyFans novel forthcoming...